Not that it matters, I suppose. If you’re still out there, pray for me. I got lost somewhere and am trying to find my way back.

Friday of the First Week in Lent

if today you hear his voice harden not your hearts.

Not hearing much of anything this week–not beyond the ordinary sounds of a house during my daughter’s half-term break. Half-term for a lone working parent is its own kind of penance, I suppose. It hasn’t helped that she’s been sick, nor that I had a full day of meetings yesterday, nor that I am under a significant amount of pressure from various work-related angles. It also doesn’t help that she has an older sister who demands a considerable amount of attention and help with personal care. All in all, half term is a week that is entirely outwardly-focused and devoid of any time for the solo walks that allow my brain to keep functioning. It is a step beyond penance into the realm of the psyche-destroying and soul-obscuring. Which is where I am now: mentally tangled and soul-obscured.

The thing is, I am uneasy about the obsession with our happiness, the thirst for self-fulfilment that is all but normative in the modern, majority world. I don’t think it is our proper orientation–more like a broken compass that leads us ever astray. The path to happiness and self-fulfilment is not in the pursuit of either of those things. Where I am stuck at the moment is in the process of working out how to live in a way that leads to peace, which is not the same as either happiness or self-fulfilment. Not the same–deeper than either and essential to both. How to find peace in the midst of the stress, as I am pulled in different directions by everything and everyone around me–that’s the question. And I confess that I am no closer to answering it than I was when I first became a mother.

Sigh. It is time, now, to return to the fray and hope I am not pulled apart completely today by the forces that tug me this way and that.

Kyrie eleison.

Well, I wasn’t expecting that. Years ago–2009, to be precise–I wrote a Lenten devotional as part of my discipline for the season. I reflected on the daily Mass readings and chose a saying of the desert fathers that fit with my reflection. (In terms of the Lectionary, it was Year B(II), like this year.)

Today, I am rushing–meant to be off in less than an hour to drive 5 hours south to my in-laws. So I thought I’d pull up the entry from Saturday after Ash Wednesday, 2009. And that’s all that’s there: a brief quotation from my set text for this Lent: Isaiah 58. There’s no time for reflection now, but I feel certain that my Lent is on track.

Deo gratias.

Friday after Ash Wednesday

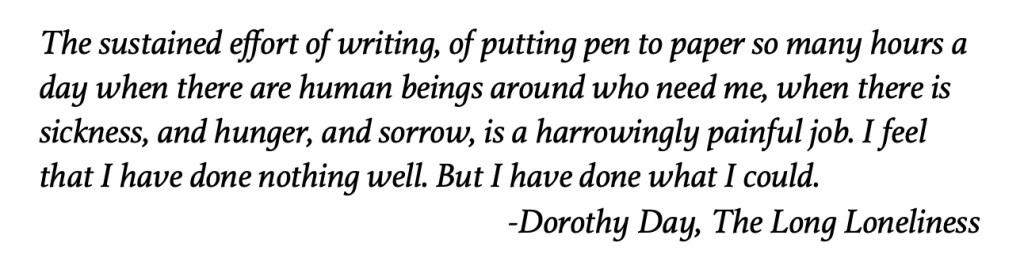

Why am I doing this? Why am I ‘putting pen to paper’, so to speak, this Lent? I am making a concerted effort to write, not only in my journal, but here, on this blog. But why? There are human beings around me, my family in the first instance, who need me. Yet here I am, sitting at the computer.

I think what Dorothy Day says earlier in the preface of sorts (‘Confession’) helps me to see a little of why I am doing this. She observes that writing the story of one’s life ‘is a confession too’. And that is one reason for writing: to admit, every day, that I am not good at this. Not good at all. I’m often tired and resentful, more distractable than usual, and I feel distinctly less-than-holy. The poor in spirit may be blessed, but it isn’t a great place to be, emotionally and psychologically speaking. Trying to do Lent properly makes me painfully aware of how lacking I am in virtue, in the fruits of the Spirit.

The writing is also, Day observes, like giving oneself away, which is what love urges us to do. I’ve never really thought about writing as a form of love, an activity of love. But if she is right that ‘[y]ou write as you are impelled to write’, it is Love, the Spirit of Love, that does the impelling.

But that is all for the morning: there are human beings stirring who need me, or they’ll miss the bus.

Thursday after Ash Wednesday

One day down. Many, many days to go. And yesterday was hard. Not because of Ash Wednesday, though the doing-without didn’t lift my spirits. Things are just generally hard in this season of my life, and I have been struggling. I feel that there ought to be something I can do to change things, or that there was something I should have done the day before yesterday, or last year, or sometime in the 1990s, that would have made yesterday less disappointing and anxiety-ridden.

But I know that’s not how it works. That’s not what the Christian life is about. It’s not about succeeding and being comfortably happy. A fair few years ago I published a book in which I suggested that holiness is in the struggle–it’s not getting to the top that characterizes Christian life, but getting up again after every setback. (If you’ve seen the 1986 film ‘The Mission’, Rodrigo’s epic hill-climb is what I have in mind.)

Not only that, though. Tough going, in the New Testament, tends to mean that you’re on the right track rather than the wrong one. I used Acts 14.22 to show this (if you’re curious, see pp. 225-226), but certainly we would not have to look further than Matthew 7.14: ‘For the gate is narrow, and the way is hard, that leads to life, and those who find it are few.’

Maybe that doesn’t sound like good news in the abstract. Maybe it sounds like bad advice, perhaps, or an encouragement to wait for heavenly joy instead of resisting present suffering. But in a situation where I am wondering what I could have done to avoid this, or what I did to deserve feeling like I do, it is the best news. Because it doesn’t mean I am in the wrong place. (Now, there are all sorts of suffering that we bring on ourselves, like a bad hangover, but that’s not what I’m talking about here.)

I’m not saying the rest of Lent is now going to be easy, or even easier. I just hope that I’ll be able to remember from one day to another that this is the right road, however much I may struggle to take the next step on it.

Ash Wednesday

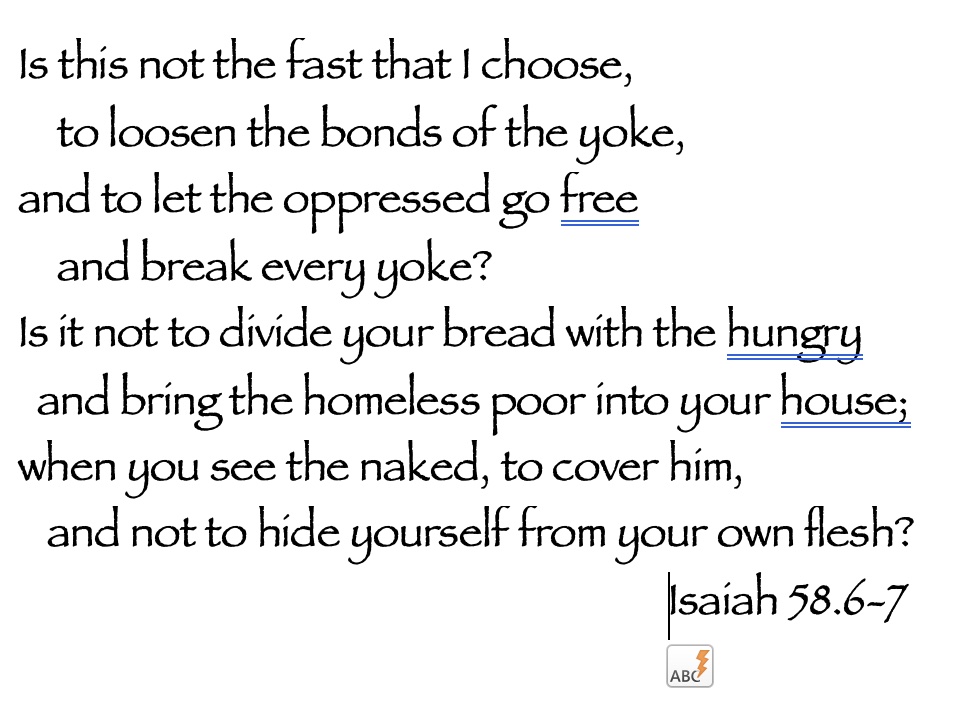

These lines from Isaiah 58 struck me a few weeks ago at Evensong: the Lord is not impressed with the showy fasting undertaken as a means to obtain the Lord’s favour and that does not alter the desires of those who fast.They still seek their own will, rather than the Lord’s. The Lord chooses another kind of fast, a fast that touches the heart of the penitent, a fast that draws them near to the hungry, the naked, and ‘the homeless poor’. Fasting is not an end unto itself. Doing without for the sake of doing without is useless, a feat of the will of the person who abstains. This Lent I will keep Isaiah 58 close at hand always, and try to remember the feast the Lord chooses.

This Lent I know I will not do perfectly. My daily posts will not be perfect–nor, it seems likely, daily. Fasting might make me irritable. I may look past those I ought to notice, grumble when I’d rather not abstain, and make excuses for myself. I will be tempted to give up on the things I have set out to do. But two things occurred to me this morning as I struggled through breakfast time without having anything to eat. First, it is bound to be awful sometimes. What sets Lent apart is that we choose to endure some awfulness for the sake of obedience to Christ. Second, the feeling that I can’t possibly do what I have set out to do is natural, appropriate, and true. I cannot, of my own strength and volition, maintain the Lenten discipline I have chosen. If I could, it would be a triumph of my will–not the fast the Lord chooses. If I succeed today, this week, or this season, it will be grace abounding in weakness, not an achievement of my own.

On the feast of St Joseph

The solemnity of St Joseph trumps Lent. No purple today; it is not Tuesday of the fourth week of Lent. (In our diocese we observed the solemnity of St Cuthbert, our patron, yesterday.) it is the feast day of St Joseph. His feast day is important enough that it has been translated, as it fell on Lætare Sunday this year.

And it should be given such special attention. ‘When Joseph woke up [from the dream in which the angel of the Lord appeared to him to say that the child in Mary’s womb was conceived by the Holy Spirit] he did what the angel of the Lord had told him to do’–that is, to marry her anyway (Matthew 1.20-21, 24).

Joseph copies God–not that Mary had been unfaithful like Israel with the Golden Calf, or like Hosea’s wife, but in appearance. For how many would have believed Joseph at the time? Whom would he tell, anyway? We are never told that he reported the dream to anyone, though it is a safe bet that he told Mary. Perhaps Mary repeated it to Elizabeth. After all, Elizabeth knew that Mary’s baby was no ordinary child.

To the rest, the world outside, how must it have looked? Either Joseph had known his betrothed before their marriage, or someone else had. I don’t imagine that anyone’s first guess would have been conception by the Holy Spirit. Only after the birth of Jesus did the angels spread the news that Isaiah’s prophecy–which the angel had called to Joseph’s mind–had been fulfilled. Only then did the wise ones rejoice to see the promised child.

But Joseph believed, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness. Rightly does Bernardino of Siena (Sermon 2, on St Joseph: Opera 7, 16. 27-30) suggest we append St Joseph to the litany of the faithful in Hebrews 11. By faith Joseph took Mary to be his wife, trusting the words of the angel of the Lord that Mary’s child would save his people from their sins.

So it is not surprising that Joseph’s foster-child, after being found in the temple by his anxious parents, ‘went down with them and came to Nazareth and lived under their authority’ (Luke 2.51). Like (foster-)father, like son. Elsewhere in Hebrews, we read that Jesus learned obedience: Jesus, the Incarnate Word of Almighty God, who, as God, owed obedience to no one. Yet he learned obedience from two people whose obedience is celebrated in the Church this week: Joseph and Mary. Today we read that Joseph ‘did what the angel of the Lord told him to do’; on Saturday we celebrate the moment Joesph’s betrothed said to the angel: ‘Let it be to me according to your word’ (Luke 1.38).

Mary and Joseph trusted what God’s messengers said to them, and they are our spiritual parents as we have been incorporated into Christ. So we should, as members of the Son they nurtured, honour them as the commandment teaches: ‘Honour thy mother and father.’ Rightly do we celebrate them, righty do these two solemnities interrupt our penance during Lent. The solemnities of St Joseph and of the Annunciation point to the great feast of the Nativity, in which we celebrate the birth of the One born to save his people from their sins by his obedience, even unto death on a cross.

The intermingling of sorrow and joy is the pattern of Christian life. We are pulled from the gloom represented by the purple cloth in the midst of Lent, and we mourn on the solemnities of the martyrs–St Stephen and the Holy Innocents at Christmas and St Mark, St Philip and St James at Easter–during times of celebration. This pattern reminds us that we are living in the time between the dawn of salvation and its consummation. And so we wait in gloom but not in despair; we wait in joyful expectation even as we do penance, for the One who has died is risen, and will come again in glory.

St Joseph, pray for us!

Thursday after Ash Wednesday

Quis ascendet in montem Domini / aut quis stabit in loco sancto suo? Innocens manibus et mundo corde / qui non levavit ad vana animam suam, nec iuravit in dolum. Ps 23 [24]: 3-4

Notam fac mihi viam, in qua ambulam/ quia ad te levavi animam meam. Ps 142 [143]: 8

The translation of ‘levavit ad vana animam suam’ I usually read renders it, ‘desires not worthless things’. So I have always thought of this quality—of the one who does not desire them—as a kind of non-distraction by useless stuff: trinkets, frippery, junk. But Psalm 142 puts it in a different light. ‘Ad te [Domini] levavi animam meam’: ‘to you [Lord] I lift up my soul’. If the soul is meant (as of course it is) to be ‘lifted up’ to God, then ‘levavit ad vana animam suam’—[having] lifted up the soul to worthless things—is nothing short of idolatry. It is not simply distraction by shiny trinkets but displacing the proper object of the soul’s desire: God. Then these are not just any worthless things. Whether or not the things mentioned are idols crafted of wood or stone, once the soul has been lifted up to them, they become idols. For that is what idolatry is: putting something else in the place of God. Compared to God, anything we desire is vain, useless. That is, nothing we desire will satisfy our soul. So the psalmist longs for God like a person in a desert yearns for water. Only God can quench that thirst. So the psalmist calls on God when his heart is numb within him. Only God saves all those who are crushed in spirit. To expect things—any things—to heal a broken heart or satisfy a thirsty soul is to try to fill a cracked jar with water: vain.

Idolatry is not a sin because God gets angry at being replaced, as if we are thereby depriving God of some necessary accolades. Idolatry is a sin because it stops us calling on God in the day of trouble, which is our only hope of rescue. And it isn’t only things that appear worthless that can be idols, of course. The most pious-seeming sacrifices can become idols if they are not offered up to God with a humble and grateful heart. All the burnt offerings continually before God (in Psalm 49 [50]) are worthless compared to ‘a sacrifice of thanksgiving’. God does not need the things we offer up. God lacks nothing: ‘if I were hungry, I would not tell you’ (Psalm 49[50]. 12). No: what God asks is this: ‘Call upon me in the day of trouble; I will deliver you, and you shall glorify me’ (v. 15).

All the practices of abstinence, fasting and almsgiving, prayer and penance, can become idols if we do them out of a desire for anything but God. The lack of food on days of fasting is a tiny taste of the ‘day of trouble’—a self-induced lack to train the soul for the real thing: a hunger we have not chosen and cannot satisfy; an emptiness not of our own making.

How will my soul know what to do in the day of trouble? Practice, practice, practice: ad te levavi animam meam, ad te levavi animam meam. In all the small wants that irk me during Lent, let me lift up my soul to the One who alone can satisfy.

Deo gratias.

Under covid’s spell

For the past ten days, I have been living in the peculiar, hazy world the virus has created for me. This is not a complaint: I know, even as I struggle to walk upstairs, that I have nothing to complain about. Getting up the stairs means I can breathe, and breathing is good. Breathing is something I have always taken for granted before. Now I am grateful for it. Grateful I can climb the stairs; grateful I don’t need oxygen; grateful I have a family around me; and grateful, of course, for the vaccine (second shot late spring), which seems to be protecting me from the worst the virus can do.

In this peculiar and hazy world, I cannot do all the things I usually do. In fact, I can do very few of them. Even writing this is tiring. I never dreamt that lifting my hands to type (on my iPad, sitting in my bed) would be tiring. But it is. Reading is a challenge. The Monday crossword took twice as long as I expected. I move slowly, when I move at all, and it takes some doing just to get going.

I suspect that I am treading the territory of a country that has temporary residents (as I hope to be this time) and permanent residents (which I may be one day, God willing, if I live long enough to wear myself out). I hope that I will be changed for the better by my visit. I know slowing down is good for me, though this isn’t the way I would have chosen to do it.

And that’s it. That’s all I can write today. In your charity, dear reader, would you pray for me, that I am changed for the better? Let me know if I can pray for you. After all, I’m not doing much else these days. ❤️

notes from the darkness

I’m staring at the pages I’m supposed to be editing. Nothing is getting through. The words are stuck somehow, stuck to the page in a way that stops me picking them up, and putting them into my mind. It’s not the page’s fault, nor the author’s. It’s my mind, blocking everything out. Maybe it’s full. I know my head hurts, but it doesn’t hurt quite enough for me to get up from the chair, go to the kitchen, and reach for the paracetamol. Not yet, anyway.

I know this feeling, and I hate it. It’s my depression. My own, personal form of that thing that follows so many people around and wreaks havoc in their lives in myriad and often unpredictable ways. It never fully goes away. It lurks in the corners and hides in the shadows, waiting for an opportunity to attack. I can almost imagine it, a little black monster leaping out and enveloping me like a cloud made of tar. Sticky. Everything slows down; my mind closes its shutters, and I am alone inside.

But I’ve got this peephole, I guess, or I wouldn’t be writing. I’d be under my desk sobbing, or diving into a book in an effort to escape. (Sometimes that works, but I have to overcome the little voice inside that scolds, ‘No, you must not do that. You have work to do.’ It’s not wrong, the voice, and yet probably it’s not helping.) No, the darkness hasn’t enclosed me yet. Maybe it won’t, not completely, not this time. I hope.

Did I mention that I hate this feeling? I hate it because I am not under my desk. That would be reason enough to call everything off, to say ‘I’m not very well’, to curl up somewhere more comfortable than under my desk and wait for the storm to pass. Once I am there, I have lost the distance between me and my depression: I have gone under like a swimmer in the LaBrea tar pits. But I am not there. So the little voice that says ‘You have work to do’ is winning. It’s not a big step from hating this feeling to hating myself for feeling it.

It’s like I am caught in a psychological riptide. Don’t swim against it; you’ll just wear yourself out. Then you’ll be swept out to sea (or under your desk) and drown. Swim perpendicular to the current until it stops pulling at you. Which way is that? I wonder. And will I be able to do any of this work while I’m swimming along parallel to the shore?

My back tenses up and the tears press hard, and I press back. I’m not going to win this one. I’m not going to get today back. It’s gone–count it amongst my many locust-eaten days. This is my own plague of locusts, the pest that ruins my crops. This is my old enemy, my shadow, my depression, tearing me apart by undoing my mind and at the same time telling me to work, work, work. I can’t work. If it were a person, I’d fight it viciously. I’d shout, ‘Why are you doing this to me?’ But it isn’t a little black monster out there, it’s a gaping hole in here, a black hole into which sunshine and certainty vanish.

If you have never been in a storm like this, I am glad for you, and I pray you never will be. As for me, I think it’s time to head for shelter.