6:05am. Wake up. Realize that the reason it feels like it’s still the middle of the night it that the 4-year-old woke us at 1:00 because she was wearing the wrong pajama bottoms. The rest of the night was not, well, restful. Hit snooze.

6:14am. Wake up, round 2. Think. No, not yet possible. Hit snooze.

6:23am. Wake up. I must get up. At this point, I still believe I can make up for lost time. Brain will maybe catch up with the body eventually, but at least the physical activity of the day must now begin.

6:25am. Stretches. Almost-yoga. I am not virtuous. I am totally dependent on doing back stretches in the morning to be able to move about normally during the day. If I don’t do them, eventually I will move in a way that would be fine for most people my age, but will result in me finding myself on the floor. So I stretch.

6:45am. Husband arrives with coffee as I am finishing stretches.

I love this man.

6:50am. 4-year-old wakes up, requires cuddle. She’s the fourth (of four!) and I know how quickly the cuddle-able stage will pass. Without really considering my lateness, I oblige.

7:15am. Now lateness is absolutely irreversible, but I am still not awake enough to take this seriously. 4-year-old announces she wants pasta for breakfast. ‘Sure,’ I say: there’s some leftover pasta from last night, and this is not a battle I ever, ever fight. I resist, if it means cooking pasta, but I surrender easily. She does not negotiate with 40-somethings.

7:25am. While said 4-year-old is eating breakfast, I begin to tease the kitchen into a state I will later find conducive to work. This involves a broom, a bit of spot-scrubbing, and getting the boys (ages 9 and 12) to help with dishes: unload dishwasher, help stray glasses and bowls to find their way into empty dishwasher. Oddly the 9-year-old is less resistant than the 12-year-old. Or maybe it’s not so odd.

Somewhere in the middle of that, make second cup of coffee. Some of it will end up spilled on the hall table in the midst of the Battle of Finding-Things-and-Departing. Never mind: 60% of it will make it to its target, and I will slowly become a functioning adult human being. (Ok, I admit this is optimistic. But I am still not admitting that we’ll be late, so optimism is pretty much my morning modus operandi, until about 8:45–the time we ABSOLUTELY MUST LEAVE if we are to be on time.)

Time passes. This is always the mystery of the morning: where does the time between 7:30 and 8:40 go? I pack up laundry to be taken somewhere else to be washed: this is an admission of defeat. I manage to get the kitchen floor looking less awful. The boys clear away a good bit of stuff in the kitchen. Someone rouses the 14-year-old, who miraculously gets up and starts getting ready for school. I pack up the girls’ backpacks. How does this all take more than an hour?

7:45-8:30. Get 4-year-old ready for school. Insist that she put school clothes on even though she insists that she’ not feeling well and can’t possibly go to school. Remind her that the alternative to teeth brushing is not to have any. Remind her that socks instead of tights are a bad idea in January. (She tried this last week: I let her have the choice, and she admitted before she even got to school that it wasn’t a good one. Mummy was right.) Agree that she can have a sticker if she does anything at all, really.

8:25. Husband takes boys and laundry. 12-year-old spends last 5 minutes at home frantically searching for his keys and phone. (Poor kid is definitely ours.) Leaves with keys, without phone, dissatisfied with his organizational skills. Blow him a kiss from the window: he needs it.

8:45. Realize that girls are going to be late. Think: these children need a new mother. One who is on time for things. Clearly the 12-year-old has inherited his organizational skills from me.

9:00. Take 4-year-old to school. ‘Will we get there before the bell, Mummy?’ she asks. ‘No, darling. The bell rang 5 minutes ago.’ She decides not to play the game where she remains just out of reach as I try to come up with some kind of choice for her to make that will allow her to get in her seat without losing. And I try not to lose my temper. But today, nothing is lost.

9:05am. Arrive at school, grateful that we live so close. Realize I am not alone in being late to school. The kids don’t need a new mum; I just need to get over it.

9:15am. Time to get 14-year-old to school. Insist she brushes teeth. Try to do too much while she is doing that. Get to school late and realize that she’s not brushed her hair. Sigh.

9:30am. Arrive back home. Find 2 loads of laundry left behind. Sigh. I face the usual choice: how much of the domestic chaos do I attempt to order before turning to the writing project before me (the one I should have finished last week)? Make the usual decision and try to order too much of the chaos, and find the day slipping away, writing project staring at me from across the kitchen table.

11:00am. Despair.

11:10am. Write the 800+ words I should be adding to some writing project or other here on my blog. Hope I will live long enough to do some writing after the children are grown.

Noon. Might as well go to Mass. Although I fear I will just hang my head and weep, I know from experience that I probably won’t. And I need to repent of my despair and self-loathing, and remember that it’s not about what I accomplish in a day. Sometimes I forget what it is all about. Somewhere between the sign of the cross and the ‘go in peace’, I usually remember.

I just hope I don’t forget it again by tomorrow morning.

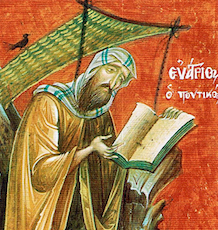

A few years ago, I came across a quotation from Evagrius of Pontus on my students’ papers. Actually, it was a paraphrase of a famous bit of Evagrius, in which he says that ‘one who prays truly will be a theologian, and one who is a theologian will pray truly.’ The impression you would have had from the context in which Evagrius was being paraphrased is that anyone who prays is a theologian. My uncertainty about that, which started as a certain skepticism (of the form ‘I do not think it means what you think it means’), has led me to wonder about the relationship between prayer and the practice of theology down the ages. Now I am a theologian, but not a historian. And this topic warrants historical and theological investigation. So I need help!

A few years ago, I came across a quotation from Evagrius of Pontus on my students’ papers. Actually, it was a paraphrase of a famous bit of Evagrius, in which he says that ‘one who prays truly will be a theologian, and one who is a theologian will pray truly.’ The impression you would have had from the context in which Evagrius was being paraphrased is that anyone who prays is a theologian. My uncertainty about that, which started as a certain skepticism (of the form ‘I do not think it means what you think it means’), has led me to wonder about the relationship between prayer and the practice of theology down the ages. Now I am a theologian, but not a historian. And this topic warrants historical and theological investigation. So I need help!