Why am I doing this? Why am I ‘putting pen to paper’, so to speak, this Lent? I am making a concerted effort to write, not only in my journal, but here, on this blog. But why? There are human beings around me, my family in the first instance, who need me. Yet here I am, sitting at the computer.

I think what Dorothy Day says earlier in the preface of sorts (‘Confession’) helps me to see a little of why I am doing this. She observes that writing the story of one’s life ‘is a confession too’. And that is one reason for writing: to admit, every day, that I am not good at this. Not good at all. I’m often tired and resentful, more distractable than usual, and I feel distinctly less-than-holy. The poor in spirit may be blessed, but it isn’t a great place to be, emotionally and psychologically speaking. Trying to do Lent properly makes me painfully aware of how lacking I am in virtue, in the fruits of the Spirit.

The writing is also, Day observes, like giving oneself away, which is what love urges us to do. I’ve never really thought about writing as a form of love, an activity of love. But if she is right that ‘[y]ou write as you are impelled to write’, it is Love, the Spirit of Love, that does the impelling.

But that is all for the morning: there are human beings stirring who need me, or they’ll miss the bus.

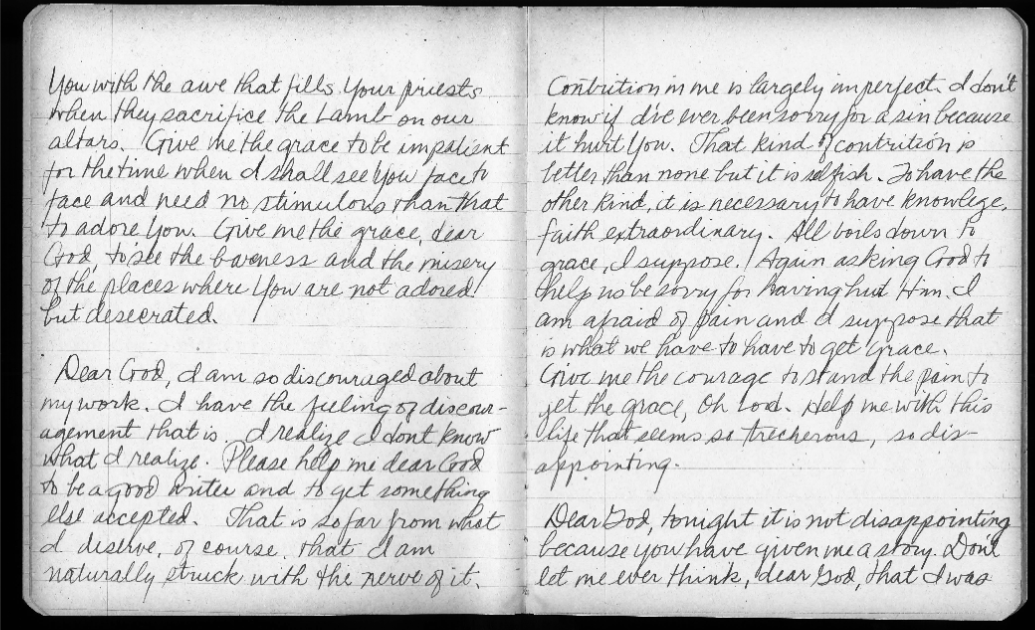

I read Flannery O’Connor’s prayer journal a few years ago. Reading the original entries, in her neat handwriting, with imperfect spelling, drew me to her in a way her fiction never did. The darkness in the stories she wrote and the grim picture of human beings and the world we inhabit haunts me; it doesn’t make me want to re-read, or to read more. My tastes, sorry as I sometimes am to admit it, run more to the likes of Jane Austen and George Eliot. Anthony Trollope, even. But Flannery O’Connor’s journal was something entirely different. It in, she recorded her struggles as an aspiring writer and a faithful Catholic woman.

I read Flannery O’Connor’s prayer journal a few years ago. Reading the original entries, in her neat handwriting, with imperfect spelling, drew me to her in a way her fiction never did. The darkness in the stories she wrote and the grim picture of human beings and the world we inhabit haunts me; it doesn’t make me want to re-read, or to read more. My tastes, sorry as I sometimes am to admit it, run more to the likes of Jane Austen and George Eliot. Anthony Trollope, even. But Flannery O’Connor’s journal was something entirely different. It in, she recorded her struggles as an aspiring writer and a faithful Catholic woman.