Mark Schrad’s op-ed piece for the New York Times is balanced and thoughtful. I am very glad he and his wife chose to have their daughter despite the diagnosis of trisomy-21. But I worry about the way this conversation is going. I worry, because there is a significant difference between the choice to end a pregnancy and the choice not to have a particular baby.

A few years ago, I reviewed Judith Butler’s Frames of War for Modern Theology (27 (3):540-542). As usual, Butler’s writing is challenging and thought-provoking, and covers a wide range of terrain. But one claim in particular stood out to me (and I refer to it in the review): the shift from seeing others as occupying the same moral and political space (i.e. being ‘modern’) to seeing them as outside that space allows us to disregard their common humanity. Now, that is a gross oversimplification, I am sure, of Butler’s nuanced proposal. Yet the basic idea, that the liberal subject is only able to be a party to the waging of war if a sort of shift takes place psychologically, is one of the conclusions of the book. Butler urges us to resist this shift.

What on earth, you might ask, does that have to do with abortion? Butler would surely argue for the woman’s right to choose in every case–or would she? In the event of an unwanted pregnancy, certainly. But once the pregnancy has been accepted and a baby is on the way, the moral ground that we are on changes. Pre-natal testing happens in order for us to find out what sort of baby we’re having and gives us the basis on which to choose whether or not this baby is one we want. The diagnosis, in the case of a baby with Trisomy-21, provides the pivot-point on which we are invited to shift our perspective: the baby would be ‘baby’ if s/he were healthy; the baby with Trisomy-21 loses the claim on our care because s/he is not ‘healthy’ or ‘normal’. That is exactly the shift that we ought to resist.

Having said that, I would add that all those who agree on this question ought to be working very hard to make life with a child (or adult son or daughter) conceivable as good. There is no getting around the fact that raising a child with Trisomy-21 (not to speak of a whole range of more serious diagnoses) will be challenging, and often (but not always–lots happens in the raising of typical kids) more challenging than raising a child with a standard set of chromosomes. We who claim that the child with Down Syndrome ought to be welcomed as warmly as the ‘typical’ child have then to share in the responsibility for loving and supporting that child and his or her family.

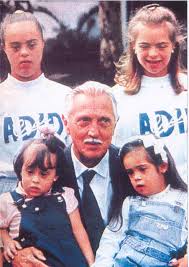

Jerome Lejune–in the centre of the photo here–did not intend for his work on the chromosomal abnormality that causes Down syndrome to be used to eliminate Down syndrome. He surely would have admitted that it’s not an easy road, and no one can walk it alone. But he would have urged us to see that which many of us who are raising (or have raised) children with Down syndrome have learned: it is not an impossible road, and it is one that can be very beautiful, if we have the eyes to see it.

Jerome Lejune–in the centre of the photo here–did not intend for his work on the chromosomal abnormality that causes Down syndrome to be used to eliminate Down syndrome. He surely would have admitted that it’s not an easy road, and no one can walk it alone. But he would have urged us to see that which many of us who are raising (or have raised) children with Down syndrome have learned: it is not an impossible road, and it is one that can be very beautiful, if we have the eyes to see it.

I cried when I saw the photo of that very small boy washed up on the beach in Turkey. How could I not? My own so small girl went to school this morning, dressed in her uniform, curls bouncing behind her. That is how it should be. Yet so many parents are struggling just to get their children to safety. As a parent, I am heartbroken. As a citizen of the so-called developed world (developed technologically, perhaps, but downright backward in its values), I am ashamed of us. How did the world get to be like this? In the words of Cardinal Altamirano at the end of The Mission: ‘Thus we have made the world. Thus have I made it.’

I cried when I saw the photo of that very small boy washed up on the beach in Turkey. How could I not? My own so small girl went to school this morning, dressed in her uniform, curls bouncing behind her. That is how it should be. Yet so many parents are struggling just to get their children to safety. As a parent, I am heartbroken. As a citizen of the so-called developed world (developed technologically, perhaps, but downright backward in its values), I am ashamed of us. How did the world get to be like this? In the words of Cardinal Altamirano at the end of The Mission: ‘Thus we have made the world. Thus have I made it.’